I’ve been traveling the Appalachian Mountains all of my life, first in the family station wagon, then on my motorcycle. It’s gorgeous country, and the people who call it home are often misunderstood. I know this because they are my people.

Growing up in central Ohio our county was bordered to the east and south by the officially-designated Appalachian region. Our community ethos was tied to the land since it was dominated by people who farmed, even if they had paid employment elsewhere.

At harvest time kids were excused from school to help bring it in, and many of the boys earned money by trapping rabbit, fox, raccoon, and beaver in the winter.

Mamaw and Papaw

My most important tie to the culture and history of Appalachia was family, especially my grandparents, whom we called Mamaw and Papaw—normal hillbilly grandparent names, in case they are new to you. Don’t wince when I use the term “hillbilly,” since Mamaw and Papaw described themselves that way.

The Blackburns, Varneys, Thackers, and Justices made their lives as farmers, coal miners—and yes, moonshiners—before WWII opened job opportunities to them in the nation’s munitions plants and armed services. The WWII diaspora is how many hillbillies found their way to our rural Ohio community, where there was a small Air Force base and other “day jobs.”

The Blackburns, Varneys, Thackers, and Justices made their lives as farmers, coal miners—and yes, moonshiners—before WWII opened job opportunities to them in the nation’s munitions plants and armed services. The WWII diaspora is how many hillbillies found their way to our rural Ohio community, where there was a small Air Force base and other “day jobs.”

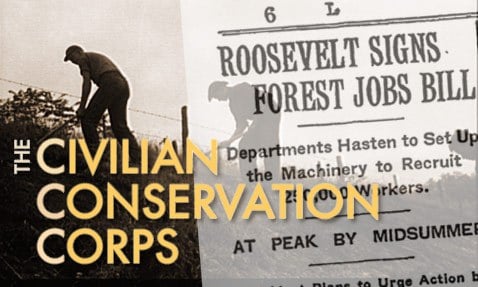

My grandparents barely survived the Great Depression, and teenaged Papaw was able to feed his parents and eight siblings by enrolling in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal program, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). When the war broke out he was inducted into the Navy.

So grateful were my Blackburn great-grandparents for the New Deal that they named one of their boys “Franklin Delano Roosevelt Blackburn.” Not Franklin Delano” or a token “Franklin” mind you. They took the name lock, stock, and barrel. We called him “Uncle Rosie.”

Junior motherhood

I was the eldest of three children. Like eldest daughters since time immemorial I was expected to be a “junior mother” to the younger kids. This didn’t come to me easily or with good grace. As a matter of fact on the first day of school I lied to my teacher and classmates by telling them I was an only child!

If both of my parents had to work in the evening, I was technically the babysitter, but I really just wanted to read my books, not break up squabbles and get them bathed and into bed at the right hour. My brother and sister turned out to be terrific adults—they’re just lucky they made it that far under my lack of supervision.

Weekends on the farm

Corn bread in a cast iron skillet

Weekends at Mamaw and Papaw’s farm were the good life for me. They were in charge of us all, and junior mother was off duty.

I rode the pony in the barnyard and out into the fields while Papaw did chores. He taught me some advanced animal husbandry, like dehorning and docking the tails of sheep.

I not only saw cattle, sheep and horses breeding and giving birth, I also tagged along when Papaw took one of his steers to the slaughterhouse. Yes, that included the killing floor as a captive bolt pistol was matter-of-factly placed to its forehead.

The circle of life.

After a day outdoors I watched Mamaw work her country-cooking magic with cast iron cookware. I cook exclusively with cast iron today.

On Saturday nights, Mamaw would teach me a new crochet technique while we all watched Hee Haw. The folksy variety show was their respite from unrelenting lives. They never missed it. Papaw reclined in a dark brown naugahyde La-Z-Boy with a TV tray to his right, which held an aluminum tumbler of iced off-brand cola. On the other side of his TV tray sat Mamaw in a swivel rocker, surrounded by the tools and spools of her passion: crocheting and knitting.

Mamaw was a prolific fiber artist and Papaw was an animal lover, traits I inherited from them in spades.

Hillbilly-in-hiding

As a pre-teen I became class conscious. While Mamaw and Papaw could call themselves “hillbillies,” I noticed that when others said it, they lacked kindly intent. I didn’t want that social stigma.

As a pre-teen I became class conscious. While Mamaw and Papaw could call themselves “hillbillies,” I noticed that when others said it, they lacked kindly intent. I didn’t want that social stigma.

That’s when I stopped watching Hee Haw and singing along with Papaw’s hillbilly songs like Rosenthal’s Goat and Three Nights Drunk—a funny song that I never knew was about marital infidelity until I heard it as an adult.

As half hillbilly I stopped talking about what happened out on the farm, other than riding my horse (I outgrew the pony). One example of my clandestine weekend adventures was the farmyard chicken slaughter. Three elements left a lasting impression:

- Mamaw told me that one of the first things she learned to do as a child was wring a chicken’s neck, but I was thankfully spared a demonstration; instead, Papaw chopped their heads off with a hatchet. So yes, I truly know what’s meant by “running around like a chicken with its head chopped off.”

- My uncle brought a headless chicken over to me, his big hands pressing its ribs together to move air through its windpipe. The moving air made the dead chicken sound just like a live one, bwwaaaaaaaaaaaakkkkk, bwwaaaaaaaaaaaakkkkk.

- The stench of a bird being scalded in boiling water to make the feathers easier to pluck.

To this day I shun chicken. I think more of us would be vegetarian if we had to do the dirty work.

Well, either vegetarian or less wasteful with our food.

Colorful speech

As a voracious reader and student of language I sucked up Appalachian witticisms with the gusto of a shop vac, and my family was a bottomless well of colorful speech.

With my newfound class consciousness I censored the expressions I learned from my family in favor of the “proper speech” that I picked up in books and school. I’d occasionally drop a hillbilly saying like, “that dog don’t hunt” or “as happy as a pig in shit,” which always took listeners by surprise.

Over time I’ve come to embrace these colloquialisms. Just last week I said, “I’d like to jerk a knot in his tail” within earshot of a British friend and it made him howl with laughter.

Once I got a driver’s license my life took a direction of it’s own. I had less and less time for family, and a heightened tendency for eye-rolling when Papaw trotted out an old tale from “the hills.”

Because the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice, my boys are now doing the same when I ramp up one of my own stories from the road.

The gift of loving fortitude

I’m always nostalgic in January since it’s my birthday month. Looking back at the heroic lives my grandparents led, I am awed and inspired, not ashamed.

I come from sturdy stock. Papaw didn’t get past the eighth grade, and while Mamaw finished high school, women earned 59 cents on a man’s dollar in 1964—her prime working years. Despite having no bootstraps to pull themselves up by, they managed to raise a family and send a little something back home to those who had even less.

I’m one of many beneficiaries of their values and priorities. In addition to taking us in on the weekends, they helped raise Mamaw’s youngest sister while another of her sisters was in a TB sanitorium, and they adopted and raised one of their grandchildren when he was about seven years old.

Last spring, en route to visit Mamaw’s youngest sister in Kentucky, I made a detour to see the coal camp where Mamaw and Papaw grew up and where my mother was born.The mines are long closed; everyone who could find a better life left long ago.

That visit was the beginning of a personal odyssey for me as I discovered the Stone Heritage Museum that preserves the history of the coal camps and people who called them “home.”

- Here I am in McAndrews

- Coal Company in Stone, KY

- Museum collection quilt

- In the museum collection

I’ll tell you more Appalachian stories this year, since I’ve been on a “roots quest” of late. Stay tuned. Better yet, subscribe to my list and you won’t miss a thing.