I recently spent a week in Kentucky with my Great Aunt Buntin in the video above. She is the youngest and only surviving sibling of six, all of whom born in the 1920’s and 30’s in a Kentucky coal camp near the West Virginia state line.

Coal camp life was tough, yet Buntin recalls some happy times and feisty memories of learning how to stand up for herself, and to make do with what she had.

When Buntin talks about “Versie” she is referring to my grandmother, whom I called “Mamaw,”and wrote about in this post. I hope you’ll watch the video—she talks about Mamaw shooting a tree rattler with a shotgun!

What were coal camps?

When I said Mamaw and Aunt Buntin were born in a “coal camp,” I hope you note the temporary connotation of the word “camp” compared to “town” or “village,” or even “hamlet.” The explanation is straightforward. Coal companies set up cheap housing—bordering on temporary—since their operations were temporary; they sold out and moved on once the coal seams were thinned or exhausted.

Miners lived in the coal camps so they could walk to work. There were no roads into the mines in the early days, since coal itself was moved by rail. The camps eventually grew into villages and towns, but the name “coal camp” stuck, along with the temporary mindset.

Everything about the extraction economy was short-sighted, provisional, and unregulated. Timber, railroad, and mining operations destroyed the natural environment and as a result, rainstorms were often violent and deadly. Mamaw once told me that their coal-company-owned house slid off its foundation in a mid-night cloudburst and her family barely escaped from their beds with their lives.

Eventually the company decided to shore it up where it landed instead of securing it with a proper foundation.

Camping, indeed.

Even 100 years later, flooding is a problem in the region, as you’ll see in this video:

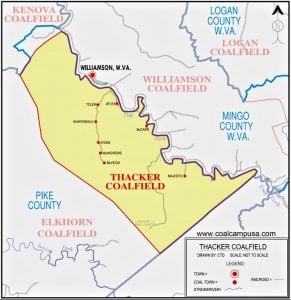

Thacker and Williamson coalfields

The maps here give you a sense of place, with a tip of the hat to the helpful website CoalCampUSA.com. Click the maps and they will pop up so you can see the detail.

The Thacker coalfield, where my family worked, was on the Kentucky side of the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River. The Williamson coalfield was on the other side of the Tug, which defined the state line with West Virginia.

Their coal camp at Stone was—and still is—an unincorporated community in the Thacker Coalfield. Stone was established in 1912 and named for the founder of the Pond Creek Coal Company, Galen Stone.

Mining companies had an interest in keeping the communities of their camps unincorporated. The lack of governmental oversight meant they could run them with a plantation mentality, something many of them understood since the coal boom occurred on the heels of the Civil War.

Life in coal camps

Mining companies ran the post office, schools, kept the peace as they saw it, and even hired pastors for the churches. Most important, they required workers to shop at company stores, with inflated pricing that often kept the coal companies afloat during the “bust” part of boom-and-bust cycles, while keeping their workers in debt and on the job. How in the world did they do this?

Workers were not paid in real legal tender. The mining companies worked on a credit system using tokens called “scrip” that resembled coins stamped with the company’s name. Since company scrip was only accepted at face value at the company’s own stores, workers often ended their week owing more to their employers than they had earned—resulting in peonage (debt servitude).

Legally, peonage was outlawed by Congress in 1867, but it wasn’t until 1938 that scrip became illegal under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

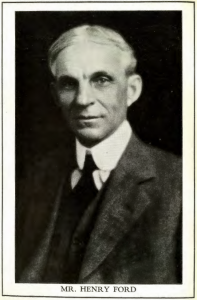

Henry Ford enters the Thacker coalfield

Henry Ford of Fordson Coal and Ford Motor Company

Of course we all know that coal fueled Industrial Age furnaces, boilers and electrical plants. What you may not realize is that coal is a basic ingredient of steel. There are different grades of coal, and the kind that was mined in the Thacker coalfield can be refined into coke, which becomes steel when combined with iron.

Since Henry Ford made cars—which required steel, which required coke and iron—it was no wonder he wanted to go into the coke, iron, steel, and transportation businesses. When Ford Motor Company experienced a work stoppage due to a coal shortage in 1922 he made his move, forming the Fordson Coal Company to buy the Stone mines and others in the region.

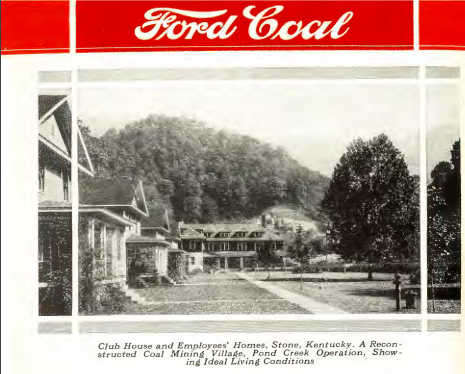

The labor uprisings in the Appalachian coalfields led to price and supply fluctuations, which bedeviled Ford and other industrialists. Ford’s approach was to improve the quality of life in the camps by improving sanitation and adding amenities like a movie theater—where my grandparents had their first date (chaperoned, of course). Ford also improved working conditions and wages, of which he boasted in marketing materials:

“These alterations in the properties and living conditions as well as the increase in wages and the steadiness of occupation render outside interference, labor trouble, and the proverbial ills of coal mining communities relatively unknown.

“One is immediately aware that he has entered the property of the Ford interests when he steps across the line dividing the Ford mining camps and villages from adjoining properties. Incidentally, all of the foregoing influences on the life of the miner have their direct effect upon production. Happy, healthy miners dig more coal.” ~Ford Coal marketing brochure

Pictured here is a snapshot from a Ford Coal brochure touting the beauty and cleanliness of Stone. What’s not reported is that the rank and file miners like my great-grandfather and grandfather didn’t live in such luxury. The homes pictured in the brochures were only within reach of management.

Ford Coal marketing brochure

Mining wars: Henry Ford exits

Buntin’s father—my great-grandfather—helped unionize the Fordson mines. He was a brave man, since coal labor-management-government fights were the largest insurrection in American history outside the Civil War. When you understand the power that mining companies had over every aspect of their workers’ lives, right down to where they could shop and their rights to free speech in the coal camps, you might have a sense for the antagonistic environment of the day.

Ford sold the mine in 1936 to Eastern Coal Company—determined to keep unions out of his organization by any means possible, including divestiture.

Matewan, West Virginia is home to the Mining Wars Museum. There, I learned a great deal about the turbulent labor-management-government clashes in West Virginia. I’ll tell you more about what I learned in Matewan in a future post.

PLEASE, if you know anything about this topic leave a comment. I’m hungry for more history!