Yellowstone National Park is an American icon. It’s what comes to mind when you think about a national park.

With summer vacation planning in full swing, I’m begging you not to shortchange yourself when you visit. Three days is the minimum stay, but spend five if at all possible. Matt and I explored the park for five days and could spend another five on our next visit!

Bison are the symbol of Yellowstone—and they are everywhere—but until you visit the park and its excellent interpretive centers (discussed below) you may not realize that Yellowstone sits atop one of the world’s largest active volcanoes. Yes, active.

The entire park sits in the depression left behind after a massive volcanic eruption. Geologists call the depression a “caldera.”

Yellowstone’s volcanic history and future

A scientist recently used seismic imaging to map the region and discovered a deeper magma reservoir below the one they already knew existed.

When—not if—Yellowstone National Park erupts again, that deeper reservoir holds enough magma to fill the Grand Canyon eleven times.

I’ll pause while you take that in.

The US Geological Service (USGS) says Yellowstone’s next eruption is likely to be hydrothermal—from shallow reservoirs of steam or hot water—rather than molten rock. When you explore the park’s famous geysers, hot springs, and fumaroles that prediction makes sense (scroll down for some of my photos of each).

There are hundreds of places where visitors are warned not to step or walk because the crust is thin and you could fall through to a boiling death.

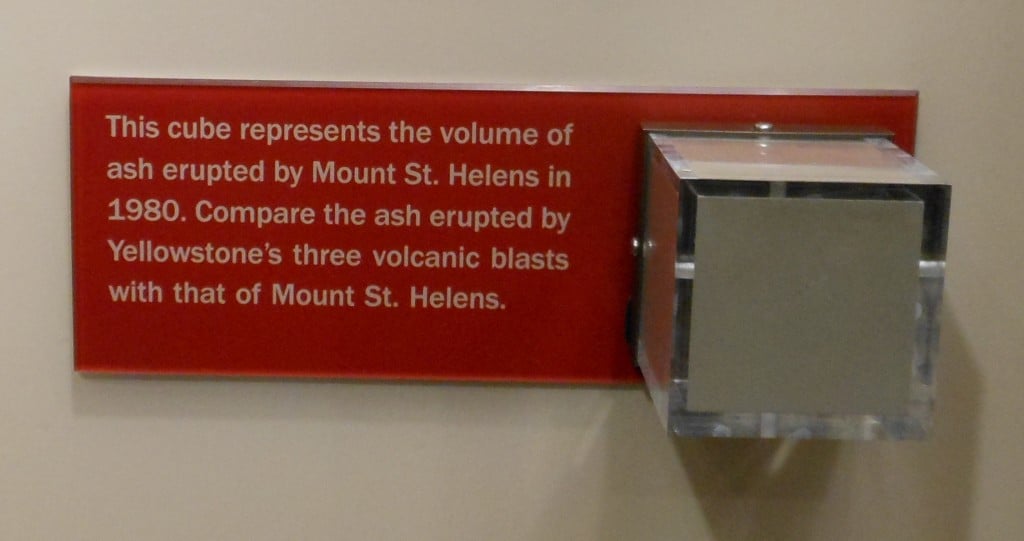

Comparing Yellowstone’s eruptions to Mount St. Helens’

The Canyon Visitor Education Center is the place to explore Yellowstone’s supervolcano and other aspects of its geology. It does a beautiful job of putting the forces of nature that created the Yellowstone caldera into context for non-geologists like me.

For example, if you aren’t familiar with the magnitude of the Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980, please familiarize yourself with it in this story and video. The Canyon Visitor and Education Center provides a visual contrast between Mount St. Helens’ eruption and each of Yellowstone’s three eruptions—which dwarf it.

For example, if you aren’t familiar with the magnitude of the Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980, please familiarize yourself with it in this story and video. The Canyon Visitor and Education Center provides a visual contrast between Mount St. Helens’ eruption and each of Yellowstone’s three eruptions—which dwarf it.

The cube to the left represents the quantity of ash that erupted from St. Helens. Now, compare it to the three large cubes in the picture below. See the corner cubes outlined in red? That’s the relative size of the St. Helens ash emission.

One St. Helens cube is 1/1000 the size of Yellowstone’s last eruption 640,000 years ago and 1/2500 of what erupted 2.1 million years ago.

This stuff enthralls me as an adult, and I am sure it would have been even more fascinating as child.

Please parents, take your kids to national parks. You could awaken in them a love for science that textbooks will never instill. And what kid doesn’t need some relief from the high-stakes-testing factories that schools have become?

Four reasons to spend a week in Yellowstone National Park

Understanding the supervolcano that formed Yellowstone’s caldera is just one example of how you could spend half a day in Yellowstone. Here’s why you need several days with the park.

#1: Yellowstone is huge. Larger than Delaware and smaller than Connecticut, the park is 3,468 mi². It takes some time to explore if you want to do more than step inside and say you’ve been there.

Yellowstone’s size is why it’s not readily apparent that you’re in a caldera—you can’t see to the other side of it!

#2 Wildlife first. More than anything, Yellowstone is a nature preserve, and that’s why it isn’t paved with four-lane highways and an outer-belt.

#2 Wildlife first. More than anything, Yellowstone is a nature preserve, and that’s why it isn’t paved with four-lane highways and an outer-belt.

Wildlife takes precedence to every human activity. Whenever there is an animal sighting—and there are many—traffic will come to a standstill.

Yellowstone is home the the largest concentration of mammals in the lower 48 states. Most often you’ll see bison, pronghorn antelope and elk, but occasionally you’ll see bear. Although these animals have become pretty tolerant of bystanders, don’t push your luck. Obey the park ranger who is inevitably standing by making sure traffic creeps along and nobody gets hurt.

You have to plan your visit really well—entering the more remote areas of the park—and you’ll need to have a lot of luck to see wolves, mountain goats and bighorn sheep. Binoculars will help.

3. Take your time. While the park has a maximum speed limit of 45 mph, don’t count on going even that fast for any stretch of time. During the high season crashes are frequent because drivers are distracted by the sights or are exceeding the safe speed and whack into someone around a blind curve. When this happens, it can take literally hours for rescue vehicles to get to the scene.

For these reasons, the National Park Service recommends allowing 4-7 hours to drive just “The Grand Loop.”

That said, there is much more to visiting Yellowstone than driving around it. Get out of the car. Hike among the geysers. Go fishing in the Madison. Watch the Yellowstone River fall into the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone (see above a the top of this post). Flop down in a field of wildflowers and have a nap.

Modern people are suffering from nature deprivation, according to Richard Louve, who studies and writes about this extensively.

“The future will belong to the nature-smart—those individuals, families, businesses, and political leaders who develop a deeper understanding of the transformative power of the natural world and who balance the virtual with the real. The more high-tech we become, the more nature we need.” ~Richard Louve

There is even a field called “ecotherapy” that helps us restore wellbeing through contact with nature. Maybe some day your doctor will say, “Take a two-hour hike and call me in the morning.”

4. You’ll love the visitors centers. They’re staffed by knowledgable staff who truly delight in answering your questions and suggesting ways to make your visit more meaningful. A guided visit with a park ranger can be a rewarding and enlightening experience.

Old Faithful Visitor Education Center is where you’ll learn about hydrothermal features that produce the other-worldly-looking geological features in the gallery below.

NOTE: You can click on any of the photos and they’ll pop up for better viewing.

Yellowstone is always letting off steam. See Matt shrouded in it above?

We visited in mid-July and the temperatures varied a great deal, from hot to cool. Pack layers of clothes.

Other Yellowstone visitor centers

Mammoth Visitor Center. Park information, a bookstore, trip planning, and ranger programs.

Fishing Bridge Visitor Center. Exhibits about the park’s birds and other wildlife, and Yellowstone Lake’s geology, including a relief map of the lake bottom.

Grant Visitor Center (also covers West Thumb area). Exhibits describe the park’s historic fires of 1988

Madison Information Station and Junior Ranger Station. Learn more online about the Madison area National Park Service visitor facilities.

Norris Geyser Basin Museum and Information Station. Information, bookstore, and exhibits on the hydrothermal features of Yellowstone.

Old Faithful Visitor Education Center. Yellowstone’s newest visitor center offers dynamic exhibits about hydrothermal features.

Geyser eruption predictions are calculated during visitor center hours and shared on signs, by telephone recordings at 307-344-2751, or via @Twitter.com/GeyserNPS

There’s more to see in the area than the park itself

We camped at KOA in West Yellowstone, Montana. The town has a great deal to offer, including the Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center, where I’d recommend spending at least two to three hours in the morning at feeding time. This is not a zoo; it’s a place where animals who can’t survive in the wild are given a life that resembles the wild to the extent humans can make it possible. What you learn there will enhance your visit to the park.

Northeast of the park is Cook City and other little villages. Plenty of fishing lodges and some terrific motorcycling roads en route to Red Lodge, MT by way of Beartooth Pass and Cody, WY via my favorite road, Chief Joseph Highway.

If you have questions or comments about Yellowstone, please comment.